Water

Not Yet Universal: Lack of Water Access Persists at the U.S. Border

Not yet universal, lack of water access persists at the U.S. Border

SHARE

Prepared by: Zulima Leal, Abigail Pérez and Mauricio Mora

Imagine having to haul water to your house, relying on bottled water for all your basic needs, purchasing water in bulk to fill on-site water tanks or using a private well, never knowing when it might run dry or how safe the water really is to drink. Although this might sound shocking, it’s a reality for many households along the U.S.-Mexico border that still lack access to safe and reliable drinking water .

In this blog, we present estimates on the lack of access to public drinking water services for U.S. communities in the border region,1 underscore some of the challenges for providing universal water service and explore the persistent gaps in access for cities and communities designated as “colonias”—housing developments built along the border without access to basic services. To address these challenges, NADBank has been advancing water infrastructure solutions in collaboration with federal, state and local partners, helping transform the lives of thousands of families at the border.

Lack of public water services

Water access on the U.S. side of the border is estimated to be almost universal at 99.5% based on 2020 data. Despite gains in the last decades, around 32,000 people still lack access to potable water services in U.S. border communities, with half of them scattered across Texas.2

Figure 1. Access to Water Services on the U.S. Border

(Coverage and Remaining Gaps)2

Source: American Community Survey (ACS, 2020) and NADBank estimates.2

Note: The U.S. border refers to 100-km NADBank jurisdiction

The lack of service coverage reflects the enormous challenges that must be overcome to supply water to everyone. Existing infrastructure, terrain complexity and distance to the nearest public water system complicate the engineering work for extending water distribution lines to unserved areas, resulting in a high cost per connection. This task is further complicated by the challenge of finding a sustainable water supply source in a region where:

- Surface water is not readily available, as rivers often run dry or are polluted, endangering residents and ecosystems. For example, the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo, s ranked as the 5th most endangered river in America, while the Tijuana River is ranked in 2nd place due to overuse, water scarcity, poor water management and lack of investments to maintain infrastructure.

- Changes in upstream snowpacks and drought conditions reduce water availability for downstream communities at the U.S. border and trigger water curtailments. See the case of Lake Mead, where a cascade of curtailments has been triggered for communities along the Colorado River Basin, including Mexico.

- Water rights are complex. Ownership of surface water flows is buried under layers of complex international treaties and state allocations (such as those for the Colorado River and Rio Grande basin) and varies by seniority and user, as well as water source, making it even more challenging to access water supply sources to meet the needs of a community. .

Limited water availability and the absence of water rights to surface water can leave communities without access to public water services, forcing them to seek affordable alternative sources. Groundwater is often among the solutions but can also represent a significant challenge due to pollution, pumping costs and overpumping.

Disparities within cities

People residing in urban areas in the U.S. are not immune to the challenges of accessing public water services (Meehan, Jurjevich, Chun, & Sherrill, 2020), and the border region is no exception.iii We estimate that around 37% of border residents without access to drinking water services in the U.S. are concentrated in the three largest border cities (San Diego, CA; El Paso, TX; and Tucson, AZ) and in three urban areas in Texas (Laredo, Edinburg, and Brownsville), usually living on the outskirts of the city or in colonias ). Figure 2 shows the prevalent gaps in water access at the U.S. border.

Figure 2

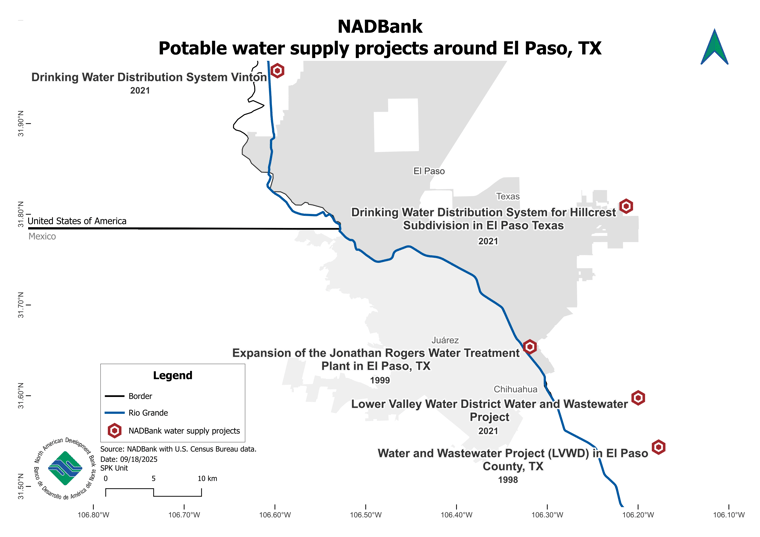

NADBank: Bringing drinking water to unserved areas in El Paso County, TX

Let’s delve deeper into the case of El Paso County, TX, where NADBank, in collaboration with federal, state and local entities, has been actively helping communities rehabilitate and replace aging water infrastructure, which not only compromises service reliability and system pressure but also loses precious water resources in a region prone to droughts, as well as expand and improve distribution systems, shift away from unsafe groundwater sources and overhaul entire systems due to inefficiencies and contamination .

In the Hillcrest subdivision, near El Paso, TX, residents were hauling non-potable water at a high price and using on-site storage tanks that posed serious health risks.iv To address these challenges, NADBank invested in the construction of a new water distribution system for 107 households. The system was connected to a master meter of El Paso Water (EPW), which now supplies, operates and maintains the service while El Paso County retains ownership of the infrastructure.

Likewise, NADBank supported the construction of a water distribution system for Village of Vinton, TX, which is serving 367 households. In this case, the Bank helped shift the water supply from groundwater with high concentrations of arsenic and pathogens to a safe and reliable distribution system operated by EPW and owned by the community.

These communities are just two recent examples of the water projects supported by NADBank throughout the county Figure 3.

Figure 3

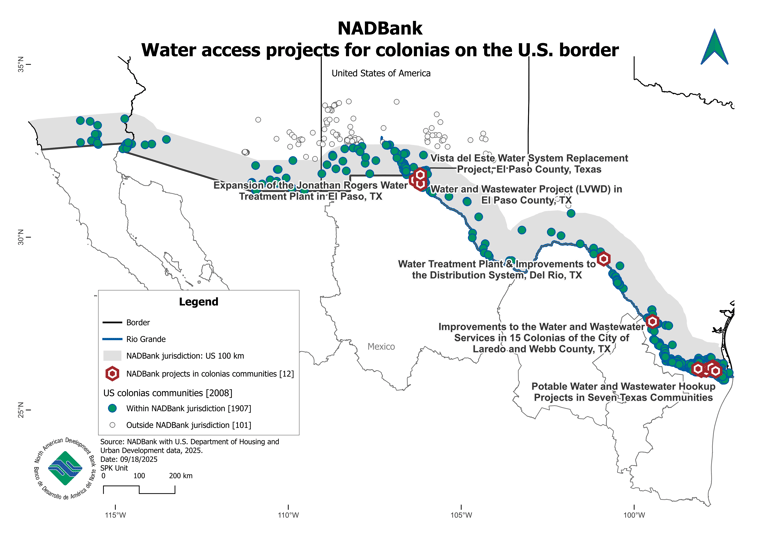

Colonias and NADBank: Bringing water access to the poorest communities

Colonias are settlements along the U.S.-Mexico border where access to basic services such as water and sewer systems, paved roads and adequate housing is limited. These communities, primarily located in rural areas and on the outskirts of cities, can vary in size. Many colonias have been established since the 1950s, a result of land being fractioned by developers without the provision of basic infrastructure (Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2015). Over 2,000 colonias are located along the U.S. border, with approximately 95% falling within the jurisdiction of NADBank .

Figure 4

NADBank has been pivotal in addressing the lack of water coverage for some of these communities. For example, the Bank provided financing that supported first-time access to approximately 900 households (3,725 residents) in 15 colonias around Laredo, TX, where distance to the closest water infrastructure kept the local utility from expanding the service. The project not only extended waterlines to meet demand but also added booster stations and storage tanks to improve water pressure and service reliability.

In addition, the Bank supported the overhaul of an aging water infrastructure system serving 340 residents in the Colonia Vista del Este near El Paso, TX. The existing system had undersized pipes that provided insufficient pressure for adequate fire response, were prone to line breaks, and were primarily located in alleys behind the houses, hampering maintenance and repairs. Expanding the capacity of the distribution system and relocating connections to the front streets has improved service quality and efficiency, ensuring safe and reliable drinking water for the entire community, as well as adequate fire protection.

Conclusion

From expanding services for first-time access to upgrading aging and failing water infrastructure, NADBank has been instrumental in providing access to safe and reliable water for thousands of families that live along the U.S. border. These advances have been made possible by partnering with the U.S. Environmental Protection Ageny, the U.S. Department of Agriculture Rural Development, Texas Water Development Board several counties, and water utilities.

References

DigDeep & U.S. Water Alliance. (2019). Closing the water access gap in the United States: A national action plan. U.S. Water Alliance. https://uswateralliance.org/resources/closing-the-water-access-gap-in-the-united-states-a-national-action-plan/

Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. (2015). Las colonias in the 21st century: Progress along the Texas–Mexico border. Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. https://www.dallasfed.org/-/media/Documents/cd/pubs/lascolonias.pdf

Meehan, K., Jurjevich, J. R., Chun, N. M. J. W., & Sherrill, J. (2020). Geographies of insecure water access and the housing–water nexus in US cities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(46), 28700–28707. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2007361117

1 The U.S. border refers to the NADBank jurisdiction within 100 km (62 miles) north of the international boundary in Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California.

2 As public data on access to drinking water is limited in the U.S., we approximate our estimates using information on housing units that lack complete plumbing facilities from the 5Y American Community Survey (ACS,2020), where we assume the absence of hot and cold running water and/or bathtub or shower refers to the lack of public water services at the household level as in DigDeep & U.S. Water Alliance, 2019 and Meehan, Jurjevich, Chun, & Sherrill, 2020. We understand the limitations of data regarding water quality, affordability and potential underrepresentation of some communities but consider this exercise a good first attempt to quantify the magnitude of the water access gap on the U.S. border. Results are estimated at the place level for the 601 places within the U.S. jurisdiction of NADBank.

3 About 73% of the water access gap in the U.S. is in urban areas (Meehan, Jurjevich, Chun, & Sherrill, 2020).

4 Estimated at $75.00 per month for 2,500 gallons of non-potable water plus additional charges for hauling services.

.png?width=1160&name=Untitled%20design%20(3).png)

.png?width=500&name=water%20and%20agriculture%20(1).png)